Since November 2022, the debate on generative AI has been … brisk. Media warnings about the end of writing (and writing teachers) are now joined with claims that AI will ruin the climate and most recently, that using ChatGPT leads to “cognitive debt” based on the recent publication by a group of MIT researchers (Kos’myna et al., 2025. As someone who has been researching the use of generative AI on the teaching and learning of writing at the higher education and K-12 levels, my email inbox quickly lit up with concerns. And since not everyone has the time to read all 206 pages of the preprint (there’s also a Time article, Chow, June 23, 2025 for additional color about the “soulless” AI writing), this is my attempt to gather some thoughts on what it might mean for educators and researchers.

First, I’d note that this is a high quality study done by researchers at a well-known research institute (MIT). However, it has not yet gone through peer review and may change in both large and small ways once it is vetted by the scientific community (one vote for changing the title + shortening the article). Specifically, researchers write that “findings support an educational model that delays AI integration until learners have engaged in sufficient self-driven cognitive effort. Such an approach may promote both immediate tool efficacy and lasting cognitive autonomy” (Kos’myna et al., 2025, p. 140), because:

Early AI reliance may result in shallow encoding;

Withholding LLM tools during early stages might support memory formation; and

Metacognitive engagement was higher in the group that started using their brains only, then moved to use LLM.

Interestingly, the phrase “cognitive debt” appears in the title and in the “preliminary” finding at the end of the (very long) article, “When individuals fail to critically engage with a subject, their writing might become biased and superficial. This pattern reflects the accumulation of cognitive debt, a condition in which repeated reliance on external systems like LLMs replaces the effortful cognitive processes required for independent thinking” (Kos’myna et al., 2025, p. 141). One commentator on the article noted that the “cognitive debt” found in the final study of only 18 participants might be attributed to the familiarisation effect because they had done the task 3 prior times using their brain, while the AI only group did the first 3 tasks with AI; engagement may have been increased due to the nature of the final task which took advantage of the prior writing (Holznagel, June 23, 2025). More important, this preliminary finding is specifically noted as requiring a larger sample size to confirm the claim. Ethan Mollick (July 7, 2025) notes in his recent post that “The actual study is much less dramatic than the press coverage,” but the discussion around it shows just “how deeply we fear what AI might do to our ability to think.” Another commentator describes some of the cultural context around the use of generative AI: “The puritanical drumbeat of productivity culture, where suffering is virtue and ease is sin”; the narrative of the decline of the latest generation of students; and the myth of self-reliance all play a role in the way the public responds to the use of generative AI (Hoerricks, June 28, 2025).

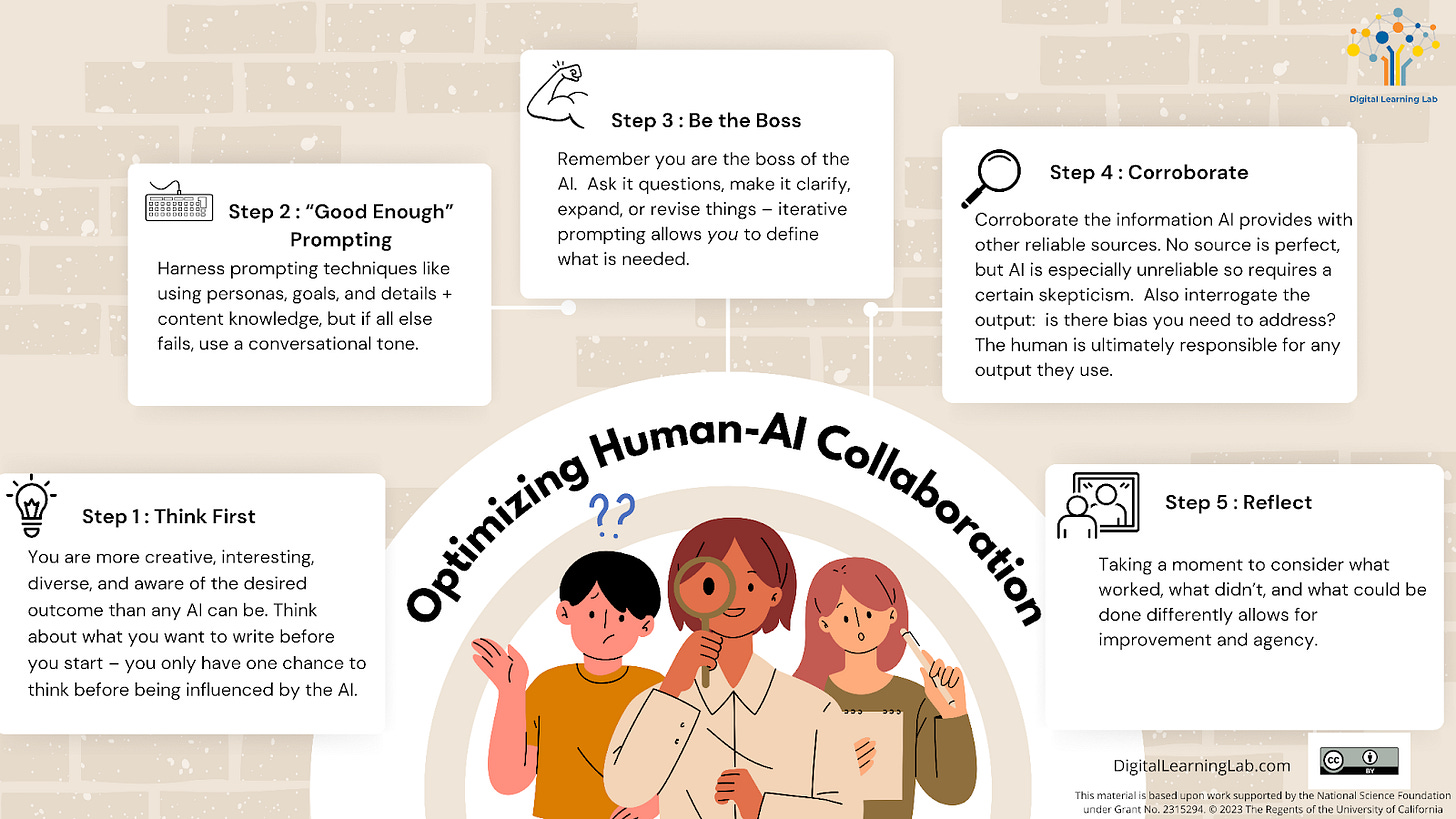

In our NSF-funded research we are finding that the most productive, learning supportive use of generative AI involves a process (see figure below) where students are encouraged to think first before turning to the AI, then after prompting they continue to iterate and “be the boss” of the AI, providing clarifying instructions until the student is satisfied with the generated output (Tate et al., 2025). While we have not checked the brain waves of students, our instructors and students agree that this process leads to more student learning than if they had simply engaged in a transactional prompt and then taken the AI output without additional engagement. This seems in line with the Kos’myna paper and leads to one of our most consistent findings: How you use the generative AI matters. Of course transactional off loading leads to less learning; we know learning requires some productive struggle. As Mollick writes, “we have increasing evidence that, when used with teacher guidance and good prompting based on sound pedagogical principles, AI can greatly improve learning outcomes.” So rather than reading this article as the death knell of generative AI in education, consider it a reminder that implementation matters and that teachers are essential to guiding the process of learning.

Another interesting note from the Kos’myna study is their finding that AI users are 60% more productive overall and due to the decrease in extraneous cognitive load more willing to engage for longer periods of time (p. 41). Instructors might find that AI, if used with precision in pedagogically appropriate ways, might scaffold a difficult and complex process like writing and make it more manageable for students who are developing their writing skills.

So my takeaway: we introduce AI with caution, under the guidance of a knowledgeable educator. We teach students how to determine if, when, and how they might choose to use generative AI, similar to how we taught students to use earlier versions of digital technology (Pinker, June 10, 2010). We do introduce them to AI literacy and practice using generative AI in schools in order to ensure that students have this opportunity regardless of their background. But we teach them to be knowledgeable, critical consumers of this and every other tool.

--Tamara Tate, Associate Director, Digital Learning Lab